History of Montpelier

ca. 1764 West Elevation

ca. 1764 West Elevation

The history of the Montpelier estate begins in 1732 when President James Madison's grandfather, Ambrose Madison, patents and settles a tract of land on Virginia's western frontier he named Mount Pleasant. Ambrose Madison would die shortly after settling Mount Pleasant and the plantation passed to his wife, Frances. Frances managed Mount Pleasant with the help of her son James Madison, Sr. (President Madison's father) until her death in 1761. While the house Ambrose Madison built for Mount Pleasant was not as grand as Montpelier, it did reflect a typical frontier homestead and included a small main house, a kitchen, various outbuildings, and slave quarters. Soon after Frances Madison's death, President Madison's father started construction on the oldest section of the existing Montpelier mansion. The house, which was probably close to finished in ca. 1764, was one of the largest dwellings in Virginia's Piedmont region and was stylistically related to other Georgian period houses in Virginia's tidewater region. The interior of the house featured four rooms and a central passage on the first floor and four bedchambers.

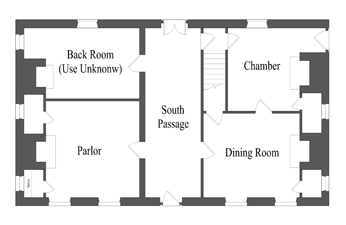

ca. 1764 First Floor Plan

ca. 1764 First Floor Plan

The first floor featured two public rooms, including a parlor and a dining room in the front of the house and what appear to be two private spaces towards the rear. The ca. 1764 version of Montpelier is particularly important because young President Madison spent much of his late childhood in the house and would go on to write some of his most important documents in its rooms.

ca. 1797 West Elevation

ca. 1797 West Elevation

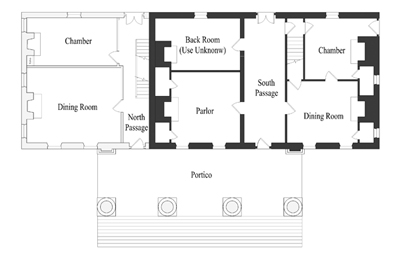

The second stage of Montpelier's development takes place in ca. 1797. Soon after the election of 1796, when his political party lost the presidency to John Adams and the Federalists, Madison left Washington and brought his wife Dolley to Montpelier to live. To accommodate his new family (Dolley had one surviving son from a previous marriage), President Madison built an addition onto his father's house. While expanding a house as large as Montpelier to serve as two separate households was very unusual, for Madison it was actually a very rational, logical decision. Because President Madison was James Madison, Sr.'s firstborn son, he expected to inherit the Montpelier mansion when his father died. So by constructing what was essentially a townhouse addition to the ca. 1764 Montpelier, Madison enlarged his future residence rather than wasting resources by building a separate house. Interestingly, while a grand new Portico worked to unify the enlarged house, the addition was clearly distinguished from the older section by slightly different shaped windows and a new main doorway that led into the President's household. On the interior, the addition included a side-passage plan with a dining room and bedchamber or parlor on the first floor and two bedrooms on the second floor.

ca. 1797 First Floor Plan

ca. 1797 First Floor Plan

Montpelier after it was Restored to its ca. 1812 Appearance in ca.

2008

Montpelier after it was Restored to its ca. 1812 Appearance in ca.

2008

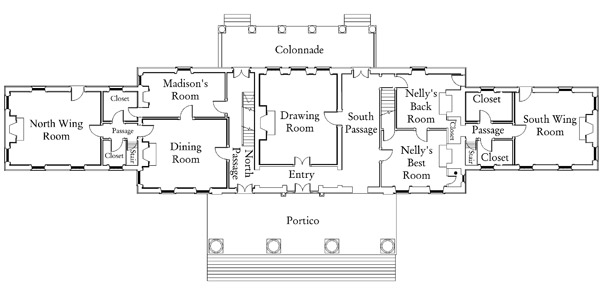

President Madison inherited the Montpelier plantation when his father died in 1801. Because he owned the house outright after the death of his father, Madison started to consider how to combine the two adjoining houses into a single architectural and social unit. While he would not start his renovations until 1808 (which was the year he was first elected president), the work would eventually unify and enlarge Montpelier by replacing all of the windows, adding a wing onto either end, and installing a large central doorway. In addition, when these additions and renovations were completed in ca. 1812, a large, central drawing room and entry space was created out of the ca. 1764 Parlor and Back Room.

The wings would also hold additional space, with each wing containing a large room, a cellar kitchen, and two closets. The south wing was also remarkable because it served as a living space exclusively for Madison's mother, Nelly. The north wing on the other hand appears to have been built to house Madison's extensive library, but it may have changed uses as the Madisons grew older. These ca. 1812 changes would be the last substantial additions or renovations made by the Madisons to Montpelier. When President Madison died in 1836, Dolley Madison inherited the property. However, she sold Montpelier out of the Madison family in 1844 after she decided to move permanently to Washington, D.C.

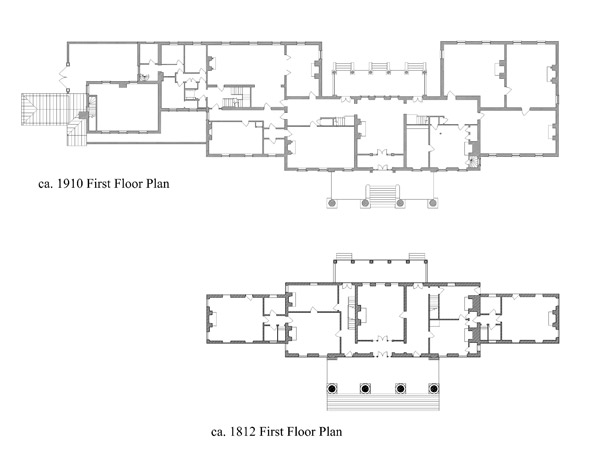

ca. 1812 First Floor Plan

ca. 1812 First Floor Plan

After Montpelier passed out of the Madison family it was sold to a succession of owners before finally being purchased by William duPont in 1901. While the duPonts would make the most significant post Madison-era changes to Montpelier, the men who owned the Mansion between the Madisons and duPonts would also make significant changes. The first owner after the Madisons was the Richmond, VA merchant Henry W. Moncure and he owned the house from 1844 to 1848. Moncure appears to have only made a few changes to the house, including possibly replastering portions of the interior.

West Elevation after the ca. 1848 Renovations

West Elevation after the ca. 1848 Renovations

Benjamin Thornton, an Englishman, purchased the house from Moncure in 1848 and owned it until 1854. Archaeological evidence suggests that it was Thornton who made extensive changes to Montpelier's portico, replaced the roofs on the wings, covered the exterior walls with a granite colored stucco and made extensive changes to the landscape that surrounded the Mansion. On the interior, Thornton also demolished the ca. 1764 Upper South Passage's Closet, removed all of the chair rails and replaced the ca. 1797 stair with a new stair.

After Thornton, Montpelier went through a quick succession of two owners in three years. First William McFarland, a Richmond, VA banker, owned the house in 1854. McFarland quickly sold Montpelier to Alabamian Alfred Scott in 1855, but Scott would only own the house for two years before selling it in 1857 to Thomas Carson and moving to Washington, D.C.

Thomas Carson was an immigrant banker from Ireland who was based in Baltimore and, after the start of the Civil War, his brother Frank appears to have been a permanent resident. Frank would continue to live, and eventually own, Montpelier until his death in 1881. The Carsons also do not appear to have made any substantial changes to Montpelier and served instead as stewards of the house.

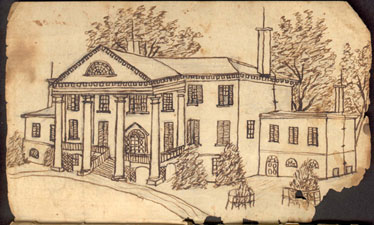

Sketch of West Elevation, Made During the Civil War

Sketch of West Elevation, Made During the Civil War

In 1881 two business partners, Louis Detrick and William Bradley, purchased Montpelier from Frank Carson's estate as a summer retreat for their families. Similar to the Carsons, Detrick and Bradley also did not make many substantial changes to the house. However, they did undertake a substantial redecorating campaign and period photos show that many of the rooms were covered with elaborate aesthetic period papers on the walls and ceilings. Additionally, nail evidence suggests that it was during the ownership of Detrick and Bradley that the closet in the Upper North Passage was removed.

Detrick and Bradley would own Montpelier until 1900, when it was purchased by William duPont through his agent Charles Lenning. Starting in 1901, the duPonts undertook a massive renovation campaign that would double the size of Montpelier and make major changes to the interior.

Comparison of the duPonts' First Floor Plan with the Madison Family's First

Floor Plan

Comparison of the duPonts' First Floor Plan with the Madison Family's First

Floor Plan

On the exterior the duPonts raised the wings to two stories and added large additions to the rear. Later, in ca. 1910, they built a large, two story kitchen wing to the northern end of the house. On the interior they added several large parlors and bedrooms as well as extensive staff housing on the northern end of the house and in the garret. The duPonts would also replace both interior stairs, and remove partitions and subdivide rooms in an effort to create a floor plan that was in keeping with a great country estate at the turn of the 20th century.

Montpelier after

the duPont Renovations

Montpelier after

the duPont Renovations

William duPont owned Montpelier until his death in 1928 and at his death his daughter Marion duPont Scott inherited the estate. While she would make many significant changes to the landscape around the mansion, including the existing steeple chase track found in front of the mansion, her only major change to Montpelier was to renovate one of the ca. 1901 salons into an Art Moderne inspired sitting room.

At Marion duPont Scott's death in 1983, Montpelier was passed to the National Trust for Historic Preservation (although they would not take possession until 1984). In 2001 an extensive architectural investigation was made into the house's architectural fabric to determine the feasibility of restoring it back to its ca. 1812 Madison-era appearance. The investigation concluded that much of the Madison-era fabric survived (although some of it had been moved and that without question the house could be accurately restored. With financial support from the estate of Paul Mellon, as well as many other foundations and individuals, including the Save America's Treasures program, the Dominion Foundation, and the Cynthia Woods Mitchell Fund for Historic Interiors, the restoration of Montpelier started in 2004 and was completed in 2009.

For more information on the history of Montpelier and for additional background on the Restoration effort please visit Montpelier.org, the website of the Montpelier Foundation.